Codes & Marks: Unit Markings

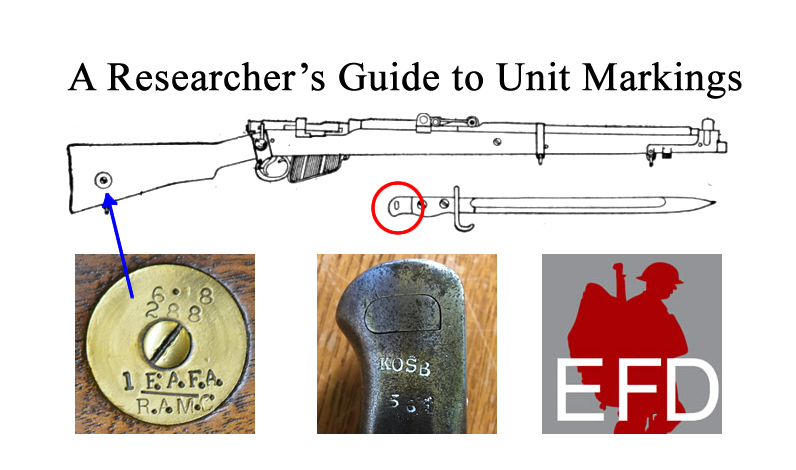

Photo notes: An armourer’s line drawing of a Short, Magazine, Lee-Enfield (SMLE) rifle, Mk III (Type One) with a Pattern of 1907 (P1907; P-07; P’07) bayonet with quillion. [1] On the lower left is a photo of a typical buttstock marking disc. The disc has been stamped 1EAFA / RAMC (1st (Battalion) East Anglican Field Ambulance / Royal Army Medical Corps.) [2] The center photo is the pommel of a P1907 bayonet marked KOSB (King’s Own Scottish Borderers). [3] The Enfield-Stuff.com logo is on the right. All items from author’s collection.

UNIT MARKINGS

If you are looking for samples of unit markings found on Lee-Enfield rifles and bayonets, the Enfields-in-Queue page in the Rifles section may be more to your liking.

If you are looking for a simple, one-stop, lookup table that lists all possible unit markings that might possibly be found on a Lee-Enfield rifle or bayonet – no such table exists.

The best that anyone can offer you is a guide to the kind of tools you will need for your search. After that, it is luck and hard work – usually more of one than the other.

UNIT MARKINGS – A RESEARCHER'S ROADMAP

[Note: the following article first appeared in the Enfield-Stuff newsletter of November 2007. It was updated August 2020.]

Abstract: In this article we will look at a 1918 SMLE (Short, Magazine, Lee-Enfield rifle) marked 1RNR and and walk through the process we used that enabled us to link that unknown mark with a regiment, the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. From 1907-1949 Newfoundland was an independent Dominion and was not part of Canada, a small fact, easily overlooked, that could defeat an unwary researcher's best efforts. The article includes a bare-bones description of the Empire's regimental organization, as well as a look at the initial popular reaction to the outbreak of war in August 1914. The article examines several books that should have a place in a researcher's library.

* * * * *

If you are fortunate enough to own a Lee-Enfield rifle or bayonet that is unit marked, congratulations!

In the years before the Great War (World War I, WWI, 1914-1919), British Empire military gear was often marked with a series of letters and numbers that identified the unit that owned the gear. In the days before computers, QR codes and RFID chips, unit markings were a way for the Quartermaster to say, "This is our stuff!" In those pre-war days the professional full-time Army was small enough (about 250,000 actives each in the British and Indian Armies) that deciphering a regimental code was not terribly difficult. In many ways it was like belonging to a college fraternity/sorority. To the uninitiated, all the Greek letters are a mystery. Once you become a member, the letters have a name, a meaning and a history.

The practice of unit marking rifles and bayonets was largely abandoned as the Great War ground on, then resumed sporadically post-war, officially and unofficially, with national and regional variations, and had largely died out by the time the Lee-Enfield was retired from frontline service.

For the collector, trying to puzzle out that cryptic code of letters and numbers stamped on a rifle or bayonet is a major challenge. While the letters and numbers might look like English, it might as well be Greek.

THE RIFLE (MUCH SIMPLIFIED)

The rifle that inspired this article is a 1918 SMLE (Short, Magazine, Lee-Enfield) Mk III*; there is a brass buttstock marking disc present marked 1RNR. Our goal is to find the who-what-when-where-why of the 1RNR mark.

The first thing to do is take a more detailed look at the rifle. For this you'll need a reference book. My first go-to book for quick work is usually Stratton's British Enfield Rifles.

|

British Enfield Rifles, Volume 1, SMLE (No.1) Rifles Mk I and Mk III Out of print - but still available on Amazon. Usually under $20 USD. |

The whole family of Lee-Enfield rifles was designed and built with interchangeable parts. The year the rifle was manufactured is not a reliable date marker, as you could easily have a 1916 buttstock affixed to a 1939 rifle. Our goal is to get an idea of when and where that rifle/bayonet was unit marked - and the only clues we have are letters, numbers, codes, runes and symbols stamped, etched, scratched, embossed, pressed or branded into the wood or metal on the rifle, as well as the component parts themselves.

The Stratton book has line drawings of each part, including the wood furniture, with detailed notes about the variations – including all eight (8!) variations of the SMLE buttstock. I find the simple line drawings well organized and easy to understand.

Our primary goal is to establish a date range for when the mark was placed. We are also looking for any national or government marks as these may be related to the unit marking. [Note: The most comprehensive list of national and government marks found on Lee-Enfield rifles and bayonets is right here on this website.]

After examining this 1RNR marked rifle in detail, there are enough 1918 dated components, stamps and markings to give me a high confidence factor that 1918 looks like a good place to start our search.

Before going further, some information about the regimental system in the British Empire is required.

A REGIMENT OF THE EMPIRE (MUCH SIMPLIFIED)

The backbone of the British Empire was the regiment. Typically, around the time of the early SMLE rifles (1903-1906) most regiments had at least two Regular battalions, with one battalion at home for training while the second battalion was semi-permanently posted somewhere else on the globe. A battalion, at full strength, was about 1,100 officers and men. Most regiments also had Reserve battalions, which were exempt from overseas service.

Generally, the unit code/mark was a simple acronym of the regiment’s name. For example, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry would be PPCLI. If the regiment had two battalions, then the battalions would be 1PPCLI and 2PPCLI. After that, it gets more complicated, but those are the basics.

Knowing this, we can infer that 1RNR stamped on the subject 1918 Lee-Enfield is probably the 1st (Battalion) RNR.

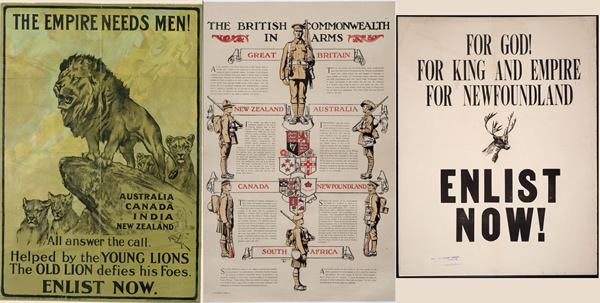

Photo notes: Left: A recruiting/propaganda poster “The Empire Needs Men!” depicts an adult male lion, symbolizing Britain, stands on a rocky outcrop. Below stand four young lions symbolizing Australia, Canada, India and New Zealand. Imperial War Museum item PST 1510. [5] Center: A recruiting/propaganda poster “The British Commonwealth in Arms” depicts New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Newfoundland and South Africa supporting Great Britain in arms. Canadian War Museum item CWM 19900348-004 [6] Right: A recruiting/propaganda poster “For God! For King and Empire. For Newfoundland. Enlist now!” The text surrounds the image of a caribou, a symbol of Newfoundland. Special Collections (Baldwin Collection), Toronto Public Library, item 1914-18. Newfoundland. Item 2. L. [7]

REGIMENTS OF THE EMPIRE (1914 - 1919)

Today, more than one hundred years after the Great War, it can be hard to grasp the scale of that conflict. The British Army went from about 250,000 professional soldiers to an army of more than three million. India alone put one million men – all volunteers - overseas. Canada and Australia put one million men in uniform and sent most overseas. The United Kingdom alone raised no less than 1761 new infantry battalions. While some of these battalions were added to existing regiments, many went to completely new units. [4]

In August 1914, there was tremendous enthusiasm for this new war. The newspapers, the generals, the politicians were certain it would “all be over by Christmas.” From all parts of the Empire, the new Dominions, Commonwealth, and Colonies were anxious to show that ‘the Colonials’ had grown up and were enthusiastic partners of the Empire. It would be a great honor to be permitted to stand, shoulder-to-shoulder, with the storied regiments of the British Empire. No one wanted to miss out on this incredible opportunity.

Britain declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. In Canada, on 6th August the Government accepted an offer from A. Hamilton Gault, a Montreal businessman, to provide $100,000 of his own money (about $2.5 Million in 2020 dollars) [5A] to immediately raise and equip an infantry battalion for overseas service. Within two weeks the new regiment had a full complement of 1098 all ranks, 1049 of which has seen previous service in South Africa or elsewhere with regular forces of the Empire. The regiment’s commander requested permission to name the new regiment after the Governor-General of Canada’s very popular youngest daughter, Princess Patricia. On 28 August, barely three weeks after the declaration of war, the brand-new regiment of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was on their way to Europe. [8]

They were not alone. The “First Five-Hundred” of the Newfoundland Regiment were right behind them.

Photo notes: Left: a map of Newfoundland; Center: the official acronym of the 1st (Battalion) Newfoundland (Regiment); Right: a group photo of No. 1 Platoon, Section 2 (1915) [13]

NEWFOUNDLAND AND THE GREAT WAR (1914 - 1919)

Discovered by John Cabot in 1497, annexed by England as a colony in 1583, Newfoundland became a self-governing Dominion in 1907, the same year as New Zealand. When war was declared by Great Britain against Germany on 4th August 1914, Newfoundland, like nearby Canada, was anxious to prove itself alongside the other Dominions. There were stark differences, however. While Canada had a population of almost eight million, Newfoundland had barely 250,000. Nonetheless, on 9th August the British government accepted “the offer of the Newfoundland Government to raise troops for land service abroad.” [9]

What does “raising a regiment” for Empire Service mean? It means that you have agreed to furnish the manpower, as well as pay for their equipment, training, transport, housing, food, supplies and care for the duration of their service. For tiny Newfoundland, that might have seemed doable if the war “was over by Christmas”, as everyone expected.

Unlike Canada’s “Princess Patricia’s”, Newfoundland did not have anyone wealthy enough to jump start a new regiment, much less call upon a battalion’s worth of experienced veterans to immediately fill the ranks. Nonetheless, the “The First Five Hundred” volunteers left St. John harbor on 4th October 1914 – two months from the day that Britain entered the war. [10] After a brief training stint in England, the brand-new Newfoundland Regiment [NFLD] found themselves ashore at Gallipoli, side by side with the ANZACs – the Australia-New Zealand Army Corps.

After Gallipoli, the Newfoundlanders found themselves on the Western Front as part of the British 29th Division and assigned to the sector of Beaumont-Hamel, France. On the first day of the (First) Battle of the Somme – July 1st, 1916 – 801 men of the Newfoundland Regiment went “over the top” in their first major engagement on the Western Front. The next morning, only 68 men were left to answer roll call – a casualty rate of more than 90% dead or wounded.

Over the next four years 6,241 men from Newfoundland joined the Regiment to serve King and Country. 1,305 – one man in five – was killed in action or died of wounds; 2,314 were wounded and survived, a total casualty rate of 60% killed or wounded – three men out of every five who served in the regiment during the Great War. [11]

In recognition of its fighting record, the Newfoundland Regiment earned the unique honor of being designated ‘Royal’ in 1918 while the war was still in progress – the only unit of any country to be so honored. [12]

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 ended the fighting, but the war was not over until the Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. The war officially over, the Royal Newfoundland Regiment returned home. The regiment was officially disbanded on 26 August 1919, almost exactly five years from the date they were founded. The war, at long last, was over. [11]

WHEN YOU'RE LOOKING UP UNIT MARKINGS, NEWFOUNDLAND (AND OTHERS LIKE IT) ARE INVISIBLE

- The unit did not exist before August 1914 - and therefore will not show up on any pre-war list of active units.

- The unit did not exist after August 1919 - and therefore will not show up on any post-war lists of active units.

- They're not British. Or Canadian or Australian or Indian or South African or New Zealand or any other major power - and therefore are not likely to be mentioned, much less included, in Official Histories of any of those countries..

- Newfoundland ceased to exist as a Dominion after the Great War. The cost of the war, followed by global economic collapse, forced the country into bankruptcy. The Legislature was dissolved; Great Britain took control of the colony in 1933.

We're going to need a reference book. Probably several.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE ONE BOOK ABOUT LEE-ENFIELD MARKINGS, IT SHOULD BE THIS BOOK

|

The Broad Arrow; 162 pages; index. If you're only going to own one book on Lee-Enfield markings, it should be this one. |

Skennerton's The Broad Arrow is my go-to book for markings. It covers inspection marks, proof, production and manufacturers markings, as well as about forty pages of unit acronyms, in alphabetical order, by country. The list includes schools, Officer Training Corps and militia. All-in-all, a must-have book that belongs on your reference shelf.

Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) is listed in the Canadian section. The Newfoundland Regiment (NFLD) is not - because 1907-1949, they are not Canadian. Nor was I surprised that RNR was nowhere to be found. There are thousands of unit markings; no book (or website) on the planet could possible cover all of them. The Broad Arrow is a very good book – but it should not be your only book.

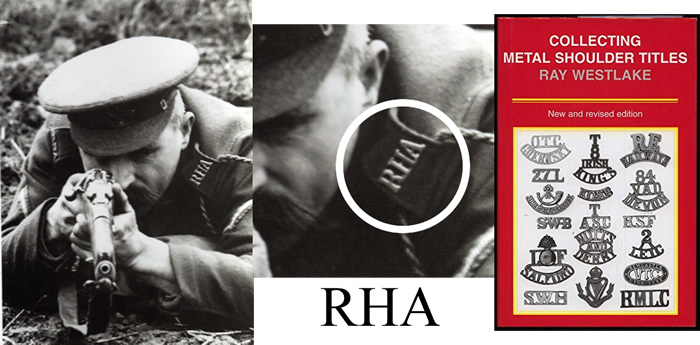

Photo notes: Left: Photo of soldier taking aim during sniping school; Center: detail of unit shoulder title “RHA” – Royal Horse Artillery; Right: Book jacket cover “Collecting Metal Shoulder Titles”. [14]

SOMETIMES, YOU MAY GET LUCKY

When I first started doing unit research, if a mark was not in Skennerton’s book, I was at a dead end. I did not know how or where to continue the search for any unknown mark. Then I got lucky. I stumbled across the photo above and noticed the RHA shoulder title, which made me curious. Like many rifle/bayonet collectors, I knew absolutely nothing about shoulder titles. I was really surprised by what I found.

I found a copy of Collecting Metal Shoulder Titles and read "The shoulder title appears to have done more to frustrate the collector than any other form of insignia. Complication is encountered when ...initials cannot be identified, or, worse still, can be applied to more than one unit… DLI, which could easily find a home with items of the Durham Light Infantry, is, in fact, the Durban Light Infantry, also of South Africa." [15]

Reading further, I discovered that "Metal shoulder titles were introduced shortly after 1881 and were at first only worn on officers’ tropical uniforms. Khaki drill uniforms were issued in India in 1885 and it was on this dress that titles were first used by all ranks. ... By 1908 metal titles were being worn throughout the British Army ... .and were worn ...in one form or another ...becoming obsolete in 1961" [16]

It took a minute for that to sink in. From 1908 through 1961 - the heyday of the Lee-Enfield rifle - metal shoulder titles were worn throughout the British Army. It dawned on me that perhaps, this book would be the book that would have a list of all the codes and marks that I would ever find on an Enfield SMLE or P1907 bayonet. I immediately purchased that book and have never regretted it.

|

Collecting Metal Shoulder Titles, Second Edition |

It is an amazing book. There are more than 2,000 unit listings, including cadets, militias, Home Guard, schools, training and Women’s units. A brief history of each unit walks you through one hundred years of consolidations, amalgamations and name changes.

Shoulder titles are not the same as unit acronyms, but often they are very similar. After a pleasant hour or two of thumbing through Collecting Metal Shoulder Titles, it was time to, at long last, solve the mystery of RNR. So you can understand my surprise when I couldn't find RNR listed anywhere. On a hunch, I then tried finding Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. (PPCLI) Not listed. That is when it dawned on me that this book should have been called Collecting British Metal Shoulder Titles.

The author, Ray Westlake, is undoubtedly the most knowledgeable person on the planet about the lineage of British units. What this reminds us is that when we look at a list - any list - you have to know not only who is included, but who is excluded. American collectors, in particular, should remember that "British" lists may exclude - or ignore - any British Empire units, even if they were British officered, trained, supplied, equipped and in the British chain of command.

SOMETIMES YOU GET LUCKY - TWICE

The wealth of information packed in the Westlake book convinced me that books on shoulder titles were a resource I had overlooked. I quickly found a book on Rhodesian [17] uniform flashes (no RNR to found there, sorry) and then a book on South African [18] militaria (where I was hoping that RNR would turn out to be “Regiment N--- (Natal?) R---), but still no luck.

Trying to identify an unknown unit mark can be like searching for a pearl buried within a giant layer cake made simultaneously by bakers from all over the planet. A comprehensive British list gives you large search slice from top (1980) to bottom (1880); a dated list (for example, 1914-1918) gives a sideways search slice. The Broad Arrow, rather than a slice, is more like big random bites of the major Commonwealth flavors.

I was looking for another book on British Empire shoulder titles, when I got lucky – again.

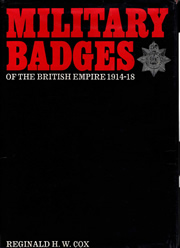

|

Military Badges of the British Empire 1914-1918 350 pages, plates, index, bibliography, appendices. |

In the hunt for more books on shoulder titles, I soon discovered that cap badges were another subset of information. Each regiment had their own distinct cap badge as well as metal shoulder titles. This was deeper than I wanted to go and did not look to be as promising as shoulder titles. However, I noticed that all the badge/button/shoulder title collectors were very focused on unit histories, nicknames, abbreviations and acronyms. So, I was prepared to be open-minded when I picked up Military Badges of the British Empire 1914-1918. It turned out to be a treasure.

The book captures the cap badges of all – all – units of the British Empire 1914-1918. The book is organized by dominions, with a brief description of each unit that existed in 1914, includes every new unit of the Expeditionary Forces mustered for overseas service, as well as all the support units, including any veterans or women’s organizations. The chaplains, nursing corps, dental units and school units are not overlooked. This is the most comprehensive list of all units from every part of the Empire that I have ever seen.

Although rifle and bayonet collectors may not be interested in what appears to be five hundred variations of Canadian maple leaf cap badge design, reading, for example, that the 239th Infantry Battalion Canadian Expeditionary Force (239 CEF) was recruited in 1916 in Nova Scotia; in 1917 became the 3rd Battalion Canadian Railway Troops (3 CRT), part of the Canadian Railway Construction Corps (CRCC) and served on the Western Front, Egypt and Salonica might turn out to be the “missing link” you’re looking for.

Fair warning: there is no alphabetical 'cheat sheet' with all possible acronyms listed. You will have to slog through, page by page, reading the descriptions and looking over the various badges and shoulder titles in order to find what you're looking for. But if the mark is a unit mark and from 1914 - 1918, that unit is in this book, just waiting for you to find it.

Which is exactly what happened when I was reading through the “Colonies, Dependencies and Protectorates” section. Fascinating reading about units you never dreamed existed. The 13,000 strong Cyprus Muleteers Corps (1915) served with the British Army in Macedonia; the Ceylon Planters Rifle Corps was attached to New Zealand’s Wellington Regiment in Egypt, Gallipoli and the Western Front. The Hong Kong and Singapore Battery saw extensive service with The Imperial Camel Corps in Egypt and Palestine. The British West Indies Regiment, founded 1915, disbanded 1921, saw twelve battalions (15,400 officers and men) serve in Egypt, Palestine, Macedonia, Mesopotamia and the Western Front. British missionaries in China recruited 40,000 men to serve in the Chinese Labour Corps [19] who, incidentally, cleaned up the battlefields of France and Belgium after the Armistice.

Finally, on page 136, I found the RNR I was looking for: “1st Newfoundland Regiment 1914. Redesignated The Royal Newfoundland Regiment and now perpetuated in The Royal Newfoundland Regiment of the Canadian Army. …Formed at the beginning of the war with the object of providing a contingent of 500 men, this gallant regiment enlisted and sent overseas 6,000 volunteers. In the terrible battles of the Somme, Arras and Ypres they lost over 1,000 killed and 2,300 wounded…In recognition of its unsurpassed fighting record, it earned the unique honour of being designed the Royal Newfoundland Regiment in 1918 whilst the war was still in progress. 3,000 other Newfoundlanders served in the British and Canadian armies. [Served] Gallipoli and The Western Front”

As a military historian, I knew about the first day of the First Battle of the Somme – 1st July 1916 – the worst day in the history of the British Army, with 19,240 dead and 38,230 wounded, a total of 57,470 casualties in one day.

I did not know about the Newfoundland Regiment. You will not find them listed in Ray Westlake’s British Battalions on the Somme, [20] a daily account that covers 616 individual infantry battalions. As the Newfoundlanders were not British Army, they were not included. Nor are they mentioned in the histories of Canadian and Indian units that fought on the Somme in 1916.

In my early days as an collector of Lee-Enfields I did not think about who a writer might include – or exclude – from their list(s). As a researcher and collector, Military Badges of the British Empire 1914-1918 helped reveal people and places I had overlooked in my research. I would not have found the 1918 1RNR without this book.

NOTES FOR RESEARCHERS - SUMMARY

- Buy good reference books. A good book will answer questions you didn’t know you had.

- Examine your rifle/bayonet in detail. Every stamp, mark, symbol has a story to tell you.

- If you can, start with a narrow search range (for example, before 1914; 1914-1918; 1939-1945, etc.)

- For any book, history or list: who is included? Who is excluded? What era does it cover?

- Be open minded about other types of militaria collectors. Their reference books might be helpful.

- Buy good reference books. Researching unit marks is a marathon, not a sprint.

- Build a time machine. If you can’t do that, then try to imagine/recreate what the world looked like at that particular time. Politically and socially, what was going on? What countries existed – or didn’t? Who was friends/enemies with who?

- Have fun. The information and books you discover today could be useful tomorrow.

Photo notes: Left: A 1918 postcard depicts a Newfoundland soldier striding across the globe from Newfoundland to Europe, with the Newfoundland flag (a British Red Ensign with the Newfoundland “Terra Nova” coat of arms) fluttering in the background while the Angel of Victory hovers in the heavens. [21] Center: Rifle buttstock marking disk stamped 1RNR below 55; caribou cap badge of the Newfoundland Regiment; Right: group photo of No. 6 Platoon, Section 6; the men are unidentified. [22]

EPILOGUE - THE NEWFOUNDLAND REGIMENT

After the War ended the people of Newfoundland sent a delegation to France, to the village of Beaumont-Hamel, and went looking for the section of trenches occupied by battalions of the 29th Division. The trenches were still there. From there one could look across the open fields - the killing grounds - and see the German trench line, just a short walk away.

The families of Newfoundland bought the land, about seventy-four acres, that their sons, their fathers, their children, their uncles and their friends had died on. Tiny Newfoundland, all on its own, created the Newfoundland Memorial Park, as a memorial to all Newfoundlanders who fought in the Great War, particularly those who have no known grave. The Newfoundlanders also acknowledged the men who fought beside them, the 1st Battalion King's Own Scottish Borderers, with 552 dead, and the Public Schools Battalion, with 522 dead. The Memorial was dedicated on June 7th, 1925.

A bronze caribou, emblem of the Newfoundland Regiment, stands atop a mound, surrounded by rock and shrubs native to Newfoundland. The caribou faces out, looking over the ground the battalions advanced that fateful morning.

At the base of the mound there are three bronze tablets inscribed with the names of 820 members of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, the Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve, and the Mercantile Marines who gave their lives in the First World War and have no known grave.

The Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial Park was designated a Canadian National Historic Site in 1997 and is now part of Parks Canada. [23]

Page Notes & Sources

[1] The drawing clearly shows (a) the buttstock marking disc, (b) the magazine cut-off and (c) the dial pointer forestock screw that affixes the (unseen) volley-sight pointer in place, all markers of an early (Type One) Mk III rifle. The bayonet pommel lacks the clearance hole (adopted 1916); the drawing is correct for quillion P1907 bayonets.

[2] The disc is dated 6.18 (June 1918); Field Ambulance/RAMC marked rifles are exceeding rare.

[3] The pictured bayonet is a P1907 with quillion; note the absence of a clearance hole.

[4] Cox, Reginald H.W. Military Badges of the British Empire 1914-1918. Pg. 145

[5] Imperial War Museum item PST 1510. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/37297 Public domain. Artist: Wardle, Arthur; Straker Brothers Ltd, 194-200 Bishopsgate, London EC (printer); Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (publisher/sponsor); (March 1915)

[5A] The original amount was $100,000 in 1914 Canadian dollars. I used an on-line currency converter to arrive at 2020 Canadian dollars.

[6] Canadian War Museum item CWM 19900348-004 https://www.warmuseum.ca/collections/artifact/1027385/ Public domain. Artist: H.M. Brock; H and C Graham Ltd., Camberwell, London SE (printer) (1918)

[7] Toronto Public Library, Special (Baldwin) Collections item 1914-18. Newfoundland. Item 2. L. https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-1914-18NEWFOUNDLANDITEM2L&R=DC-1914-18NEWFOUNDLANDITEM2L Public domain. Artist/printer unknown.

[8] Princess Particia's Canadian Light Infantry website: https://ppcli.com/ppcli-museum-description/regimental-history/

[9] Nicholson, G.W.L. The Fighting Newfoundlander, pgs. 102-103.

[10] Nicholson, G.W.L. The Fighting Newfoundlander, pgs. 114-117.

[11] Nicholson, G.W.L. The Fighting Newfoundlander, pgs. 508-509.

[12] Cox, Reginald H.W. Military Badges of the British Empire 1914-1918. Pg. 136 Three thousand other Newfoundlanders served in the British and Canadian armies.

[13] Taken by Holloway Studio (St. John's, NL). 1915. The soldiers are unidentified. Photo courtesy of The Rooms Provincial Archives Division (A 11-147), St. John's, NL. Retrieved from Heritage Canada website Newfoundland & Labrador in the First World War https://www.heritage.nf.ca/first-world-war/gallery/royal-newfoundland-regiment/index.php Retrieved August 2020

[14] Photo is a cropped section of Imperial War Museum photo Q35849; Only description is “Sniping school. 1st Army” https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205270558 RHA/Royal Horse Artillery shoulder title is identified of pg.46 of “Collecting Metal Shoulder Titles”.

[15] Westlake, Ray, Collecting Metal Shoulder Titles, Introduction, pg. 2

[16] Westlake, Ray, Collecting Metal Shoulder Titles, Introduction, pg. 1 (After 1961 metal shoulder titles were replaced with embroidered shoulder titles, a practice that continues in British service, as well as many other organizations.)

[17] Wall, Dudley, Insignia and History of the Rhodesian Armed Forces 1890-1980; 4th Edition, Just Done Productions, Durban, South Africa 2009 ISBN 978-1-920315-53-6

[18] Wall, Dudley, Starting Out Collecting South African Militaria; Third Edition; Just Done Productions, Durban, South Africa 2007 ISBN 978-1-920169-70-1

[19] Well worth your time: an English/Chinese documentary: Forgotten Faces of the Great War: The Chinese Labor Corps 56 minutes, in both English and Chinese. https://tv.historyhit.com/watch/34089395

[20] Westlake, Ray. British Battalions on the Somme, Leo Cooper Books (Pen and Sword Books Ltd., South Yorkshire, United Kingdom. 1995 308 pages; index; maps; photographs. ISBN 0-85052-374-5

[21] Artist Elio Ximenes; printed by Oilette Connoisseur, London, December 1918, one of a series of six postcards in a “Victory & Freedom” set. Each card in the set depicts a soldier from Australia, Canada, Great Britain, New Zealand, Newfoundland and South Africa in similar poses, with one foot in their home country and the other foot in the battlegrounds of Europe, set against a background of their home flag. A buttstock marking disk is clearly visible on five of the six SMLE Mk III’s depicted.

Image courtesy of TuckDB, a free database of antique postcards published by Raphael Tuck & Sons (1866-1959). https://tuckdb.org/items/117995 Retrieved August 2019:

[22] Taken by Holloway Studio (St. John's, NL). 1915. The soldiers are unidentified. Photo courtesy of The Rooms Provincial Archives Division (A 11-147), St. John's, NL. Retrieved from Heritage Canada website Newfoundland & Labrador in the First World War https://www.heritage.nf.ca/first-world-war/gallery/royal-newfoundland-regiment/index.php We note that four of five in the first row are wearing a single stripe rank chevron (lance corporal); in the top row two men of nine have a visible two stripes (corporal); and all six men in the middle row have three stripes (sergeant). Retrieved August 2020

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaumont-Hamel_Newfoundland_Memorial

Suggested Reading

|

Nicholson, G.W.L. The Fighting Newfoundlander, A History of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, Government of Newfoundland, Newfoundland (1964); McGill-Queen’s University Press (MQUP) (2006);. 658 pages. Index, bibliography, photographs, maps, appendix. |